Perhaps you’ve already heard, it will soon be compulsory for all diners to return their trays and clear their table litter from June 1st. No longer merely a sign of good table etiquette, the failure to clear all litter including, but not limited to, used tissues, wet wipes, straws, canned drinks, plastic bottles and food remnants, will result in a written warning for first-time offenders, a $300 composition fine for second-time offenders, and up to $2,000 for repeat offenders.

Set to be enforced by the National Environment Agency (NEA) after 31st August 2021, with an aim of promoting good hygiene and public dining habits, this new policy comes in conjunction with increased tray return infrastructure across the hawker centers and food courts.

Arguably on some level, this news is a large pill to swallow, and it begs the question – Are these measures truly necessary and what does it say about the civic mindedness of Singaporeans?

Before we delve any further, do the new measures truly come as any surprise? Lest not forget how in recent years, many seemingly common sense and community-centric behaviours have been further mandated by the government through hefty fines and severe consequences.

Take smoking under shelters, in your home, and outside designated corners for example. It is an undeniable truth that smoking is a grave health hazard not just to the users but to those around them, and yet despite laws which were implemented as early as 2005, it is still a common sight to see individuals smoking in corridors, toilets, coffee shops, at bus interchanges, and everywhere in between.

Still surprised by the latest measures? What about the issue of killer litter in Singapore? As our buildings tower higher and higher, the only thing that seems to change is how far down our litter has to fall. Whether it’s tissues, letters, food, pots, pans, or glass bottles, killer litter has been an issue in Singapore for over a decade with cases as recent as 2020, where the individuals hit have been severely hurt and hospitalised.

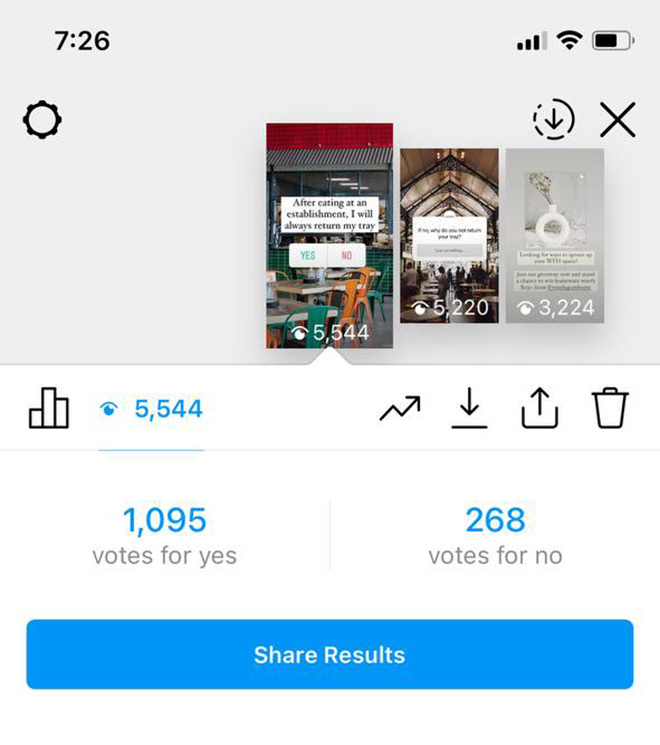

At some point or another we’ve all asked ourselves, why the specific need for a fine? Why doesn’t the government carry out widespread campaigns and other educational outreach programs to get their message across? Is there no gentler approach to dealing with issues as simple as clearing a tray? In an extremely small survey conducted on both my own, and SHOUT’s Instagram platform, I found that out of an estimated 1,268 responses, 1,095 individuals admitted to consciously clearing their trays often though not regularly, whilst about 286 others claimed to not clear their trays at all.

Looking at these numbers in a vacuum, it is easy to assume that the government’s latest measures are a severe overkill, however it is important to note that this survey is not representative of Singapore as a whole, and the majority of these participants are inconsistent in their efforts to clear their trays. As such, these numbers can easily be interpreted as none of the participants actively clearing their trays.

Looking at these numbers in a vacuum, it is easy to assume that the government’s latest measures are a severe overkill, however it is important to note that this survey is not representative of Singapore as a whole, and the majority of these participants are inconsistent in their efforts to clear their trays. As such, these numbers can easily be interpreted as none of the participants actively clearing their trays.

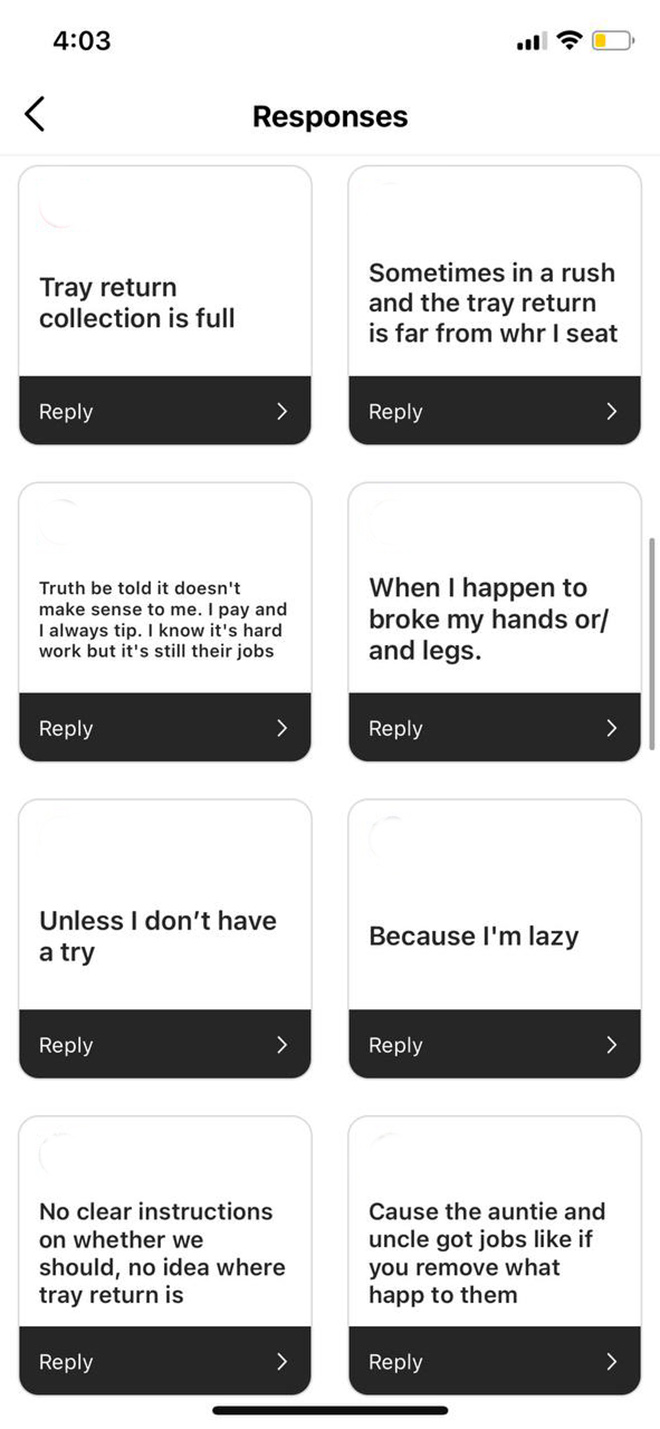

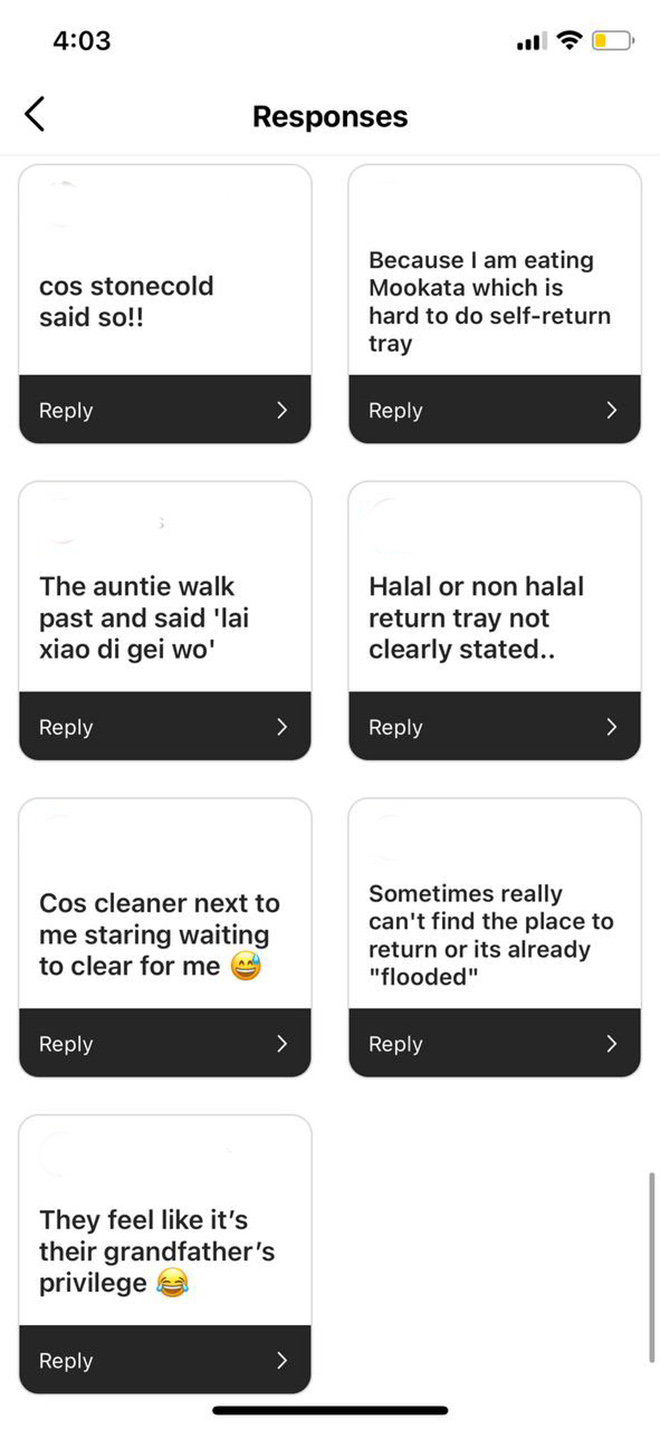

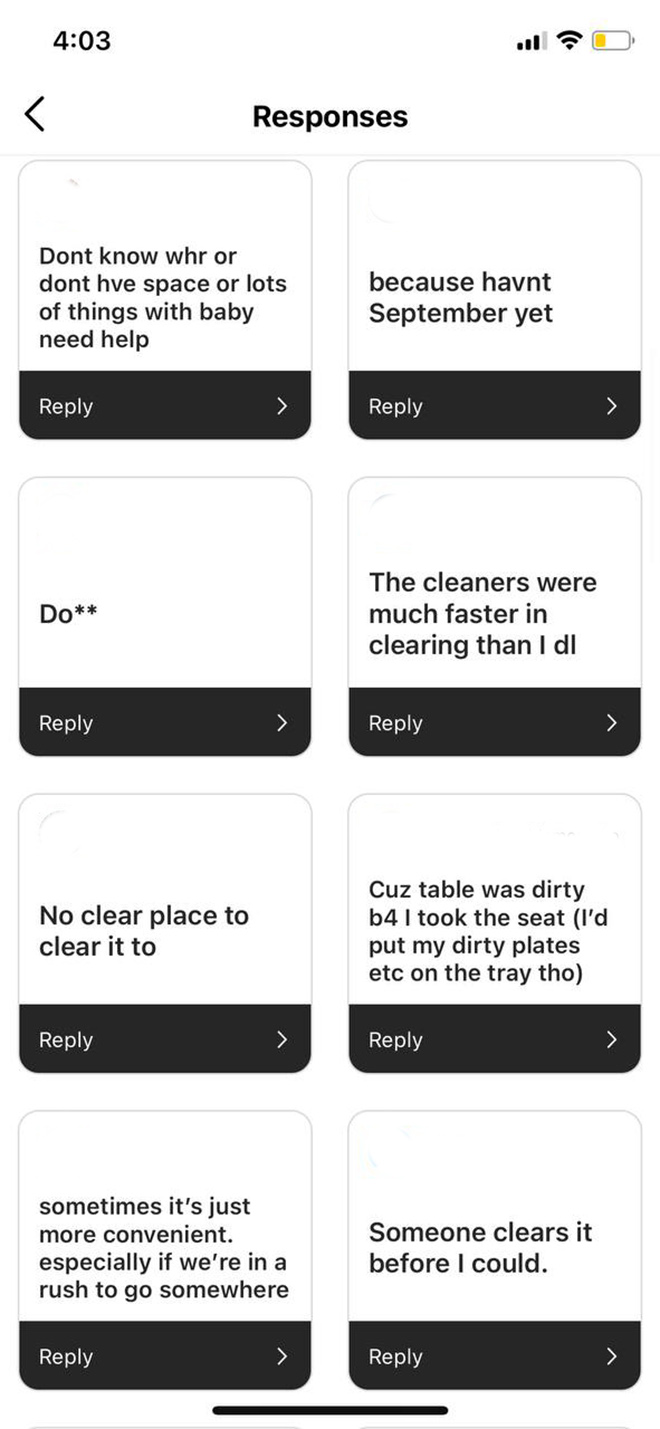

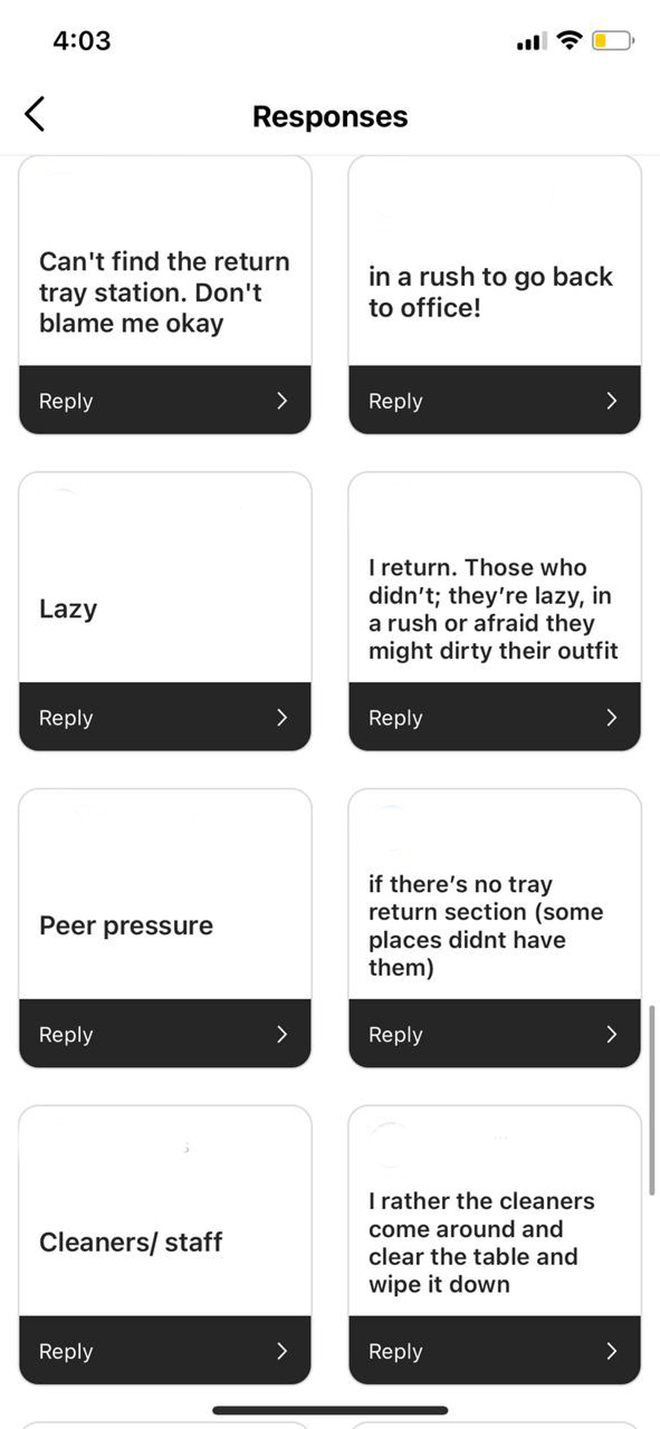

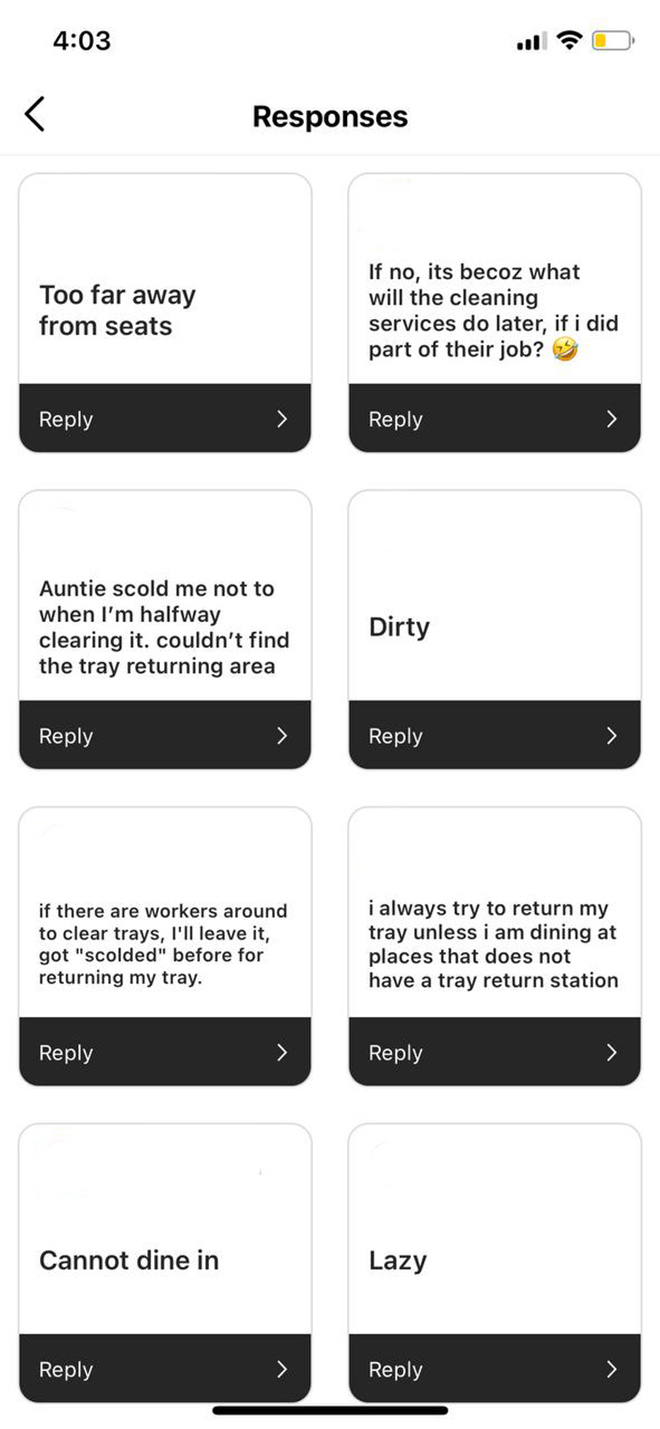

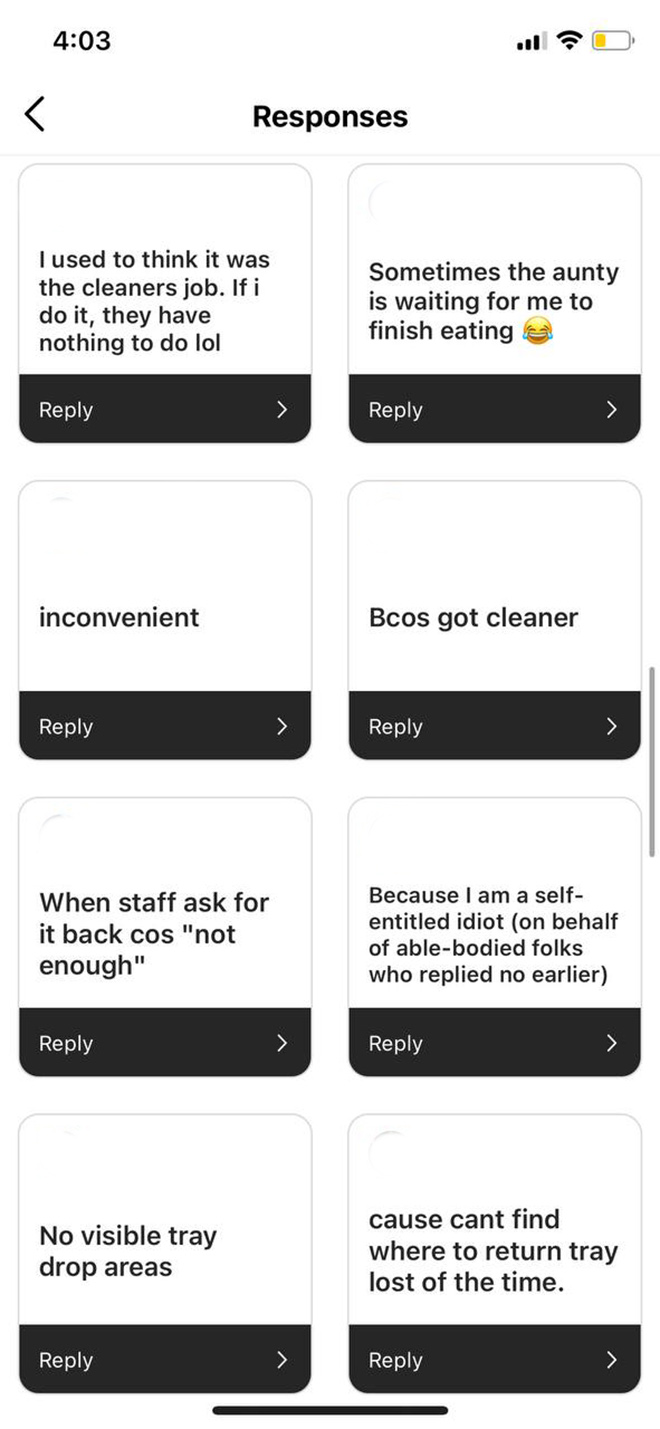

Upon further digging, I find that there are a multitude of reasons why people either consciously or subconsciously choose to not clear their trays. These reasonings include, but are not limited to, being distracted either by conversation, picking up the check, rushing back to work or to the toilet, being intoxicated, not wanting to disrupt the job of cleaners, seeing members of staff actively clearing tables, and not wanting to render their profession redundant.

Are any of these reasons wrong? In theory, no. Prior to this moment, it was never illegal to leave a mess behind at a restaurant or food court. It may under some circumstances, appear inconsiderate or disgusting, but it certainly wasn’t criminal with any severe financial consequence. When things boil down to a matter of choice, our actions tend to speak volumes. Why not choose the considerate route? Do we only do so when being considerate is the only convenient, non-punishable alternative?

Unlike what I initially thought, the issue of common courtesy and clearing trays is not at all random. Our government has been looking into and discussing such issues as early as 2013. Their first effort, known as the Return-Your-Tray initiative has been in motion for at least seven years, and even received an update in 2020. While I can’t speak for the majority of Singaporeans, I imagine there are others like me, who didn’t know such an initiative existed before today.

Where some food courts such as Adam Road Food Centre, use visual and audio reminders to encourage patrons to return their trays, others such as the one in Our Tampines Hub have a central tray return system that gives diners reward points for their efforts – and yet, despite all of this, Singapore spends close to S$120 million on cleaning public areas each year. Why? Singapore’s Minister for Sustainability and the Environment (MSE), Grace Foo seems to believe that we are “overly reliant on (our nation’s) efficient cleaning services.’’

Based on an article by Channel News Asia , it seems that even with the necessary facilities in place, NEA has observed that the average rate of tray return is at a low 30 per cent, despite 75% of Singaporeans expressing their willingness to practice good table etiquette. Does the mere thought of a civic-minded deed truly count if no action is taken? This is a question that I don’t yet know how to answer, but it is clear that Singaporeans have a long way to go in practicing their good intentions and the government intends to expedite this process through its new measures.

While most users in our Instagram survey provided reasons as to why they may forget or simply choose not to return their trays, one respondent said something rather interesting, “If you respect the place enough, be it a hawker center or fast-food chain, you wouldn’t be forgetting.” As innocent of a statement it is, the response does imply a sense of entitlement certain patrons may have, even if it is subconscious. It implies a mentality where, “I’m the customer and you work here, so you serve and clean up after me.” Though it may sound horrific, we’ve all met someone like this.

The issues which concern the root of entitlement often intertwine too deeply with a multitude of others, and then surface in the most mundane of situations like clearing a tray. So perhaps providing a surface-level solution to this issue would be irresponsible, but if you needed the reminder, clearing tables and trays is not just the cleaners job, and by doing so, each and every one of us can aid establishments in accelerating the disinfecting processes which keep all of us safe.

Take our fellow East Asian neighbour for example, Japan is renowned for its strong culture of cleanliness, which shows in its spotless trains, impeccably clean streets, and commonplace signages which remind residents to keep the area free from litter, despite the obvious lack of wastebaskets. Governed by high levels of civic-mindedness and a general wide-spread importance placed on hygiene, the Japanese take pride in having a greater sense of personal responsibility for the spaces they live in and use.

Granted not everyone is born with a ‘fully-developed civic-minded’ gene, however the Japanese specifically prioritise instilling such values into every generation at a young age. Japanese school children there are taught to clean up their classrooms, lunch tables, and even toilets in school, whilst others as young as four years old can be seen serving lunch to their peers and cleaning the tables after.

By simple comparison, one may argue that it is too late or too difficult to retrain every generation of Singaporeans on civic-mindedness through campaigns and gentle reminders alone, thus the need for brute force by the government in the form of hefty fines and stricter policy.

However, are fines and other severe consequences the only way Singaporeans can learn? Probably not, but other measures, such as the 2013 Return-Your-Tray initiative certainly require much more time, resources, and perseverance on the part of our government and community. There may be no ‘right’ way to inspire the widespread change of our habits, but what sort of messages are we, as Singaporeans and our international peers, internalising based on these stringent laws?